Sunday, 30 January 2011

A Problem You Can't Define

There is some disagreement, particularly pertinent in the recent debates about whether science conflicts with religion, about what kind of things constitute, or determine, a truth. Leaving aside the debate about the existence of intangibles, most people still accept at least two kinds of truth: empirical truths - that is, the true statements about the facts of our world - and truths by definition - that is, statements which are true purely by virtue of what they mean. It is the latter notion which I wish to discuss.

Most people agree that logical truths, such as

(1) all cats are cats

are true by definition. It does not matter what goes on in the world around us, they say; "all cats are cats" is true under all possible circumstances, and we know this just so long as we know the meanings of the words.

There is some problem with ambiguous terms which may be misleading; suppose that, in the first instance of the word "cats" we are just saying it the way Keith Richards says it, and in the second use we are talking about felines, then our statement will be false. Obviously if a word can have more than one meaning, then we need to know which meaning it has in the context.

This lead some theorizers to suggest that it is not the words (as in the sounds or symbols), but the concepts which they represent, which are to be the constituents of truths by definition. This seems more intuitive but it isn't particularly explanatory, as "concept" is just used the same way as "unit of meaning", and we need some notion of what meaning actually is. We'll come back to that later.

So how can a definition generate a truth such as in statement (1)? Gottfried Wilhelm Liebniz proposed a fundamental cleavage of "truths of reason" and "truths of fact"; that the former class were true of all possible worlds, and the latter only of our own. Logical truths, therefore, were necessary, whereas factual ones were just contingent. But how are we to test which things are true of all possible worlds, when we can only observe this one we are in? Saul Kripke's notion of necessity suffers the same paucity of information; and it is this question that the idea of "analytic" truths - that is, truths by definition - was supposed to answer. [1] [2]

Immanuel Kant proposed that an analytic truth was one in which the predicates are contained within the subject. So for instance, in

(2) all bachelors are unmarried

"unmarried" is contained within "bachelor". W.V.O. Quine pointed out that this suffers two major flaws. Firstly, it is not particularly explanatory, because we don't have a way of finding out whether a subject contains a predicate; worse, the word "contain" is surely metaphorical in this instance. In short: what does it mean for one concept to contain another, and how are we to find out whether it does in any particular instance? [3] [4]

The second problem is that we cannot apply this to statements such as

(3) either it is raining or it is not raining

in which we do not simply have the form "[subject] is [predicate]"; we rather have the form "([subject] is [predicate]) or ([subject] is not [predicate])". If such statements are analytic, then Kant's explanation will not do; and if they are not, then analyticity fails as an explanation of logical truth, at least within non-Intuitionistic logics. Furthermore, surely nobody claims that (3) was not true before the invention of language? If it had been false factually, would it still have become true analytically upon the invention of languge? If so, what is the use (or even the sense) of linguistically generated truth?

It has been suggested, alternatively, that a truth-by-definition is a statement the denial of which entails a contradiction. This is no better, however, because a contradiction is surely just a falsehood-by-definition. How do we test whether two concepts contradict each other?* And what does that mean exactly?

How do we know that a predicate is implicit within a subject? Statement (2) is of the form "(all A are B)", so its analyticity is not formally explicit. What we need is definition, because this gives us a means of transforming non-logical truths into logical truths* (and vice versa). For instance, if we can define "bachelor" as unmarried man" then we can show (by substitution) that "all bachelors are unmarried men" is synonymous with

(4) all bachelors are bachelors

and so we have a logical truth. We need, therefore, to do two things: (a) to show that logical truths such as "all A are A" are analytic, and (b) to show that definition can function without presupposing the analyticity of logical truth.

(a) Definition: The first problem is that not all terms can be explained in terms of definition, because the last term would have nothing in terms of which to be defined. This is known as the problem of the status of the primitives: if the last term is empirically understood then its meaning is uncertain, and so must be everything which is explained in terms of it. In natural English there are a vast plethora of such terms; within an artificial language, Rudolf Carnap managed to get it down to the word "is". Nonetheless, there must always be one such term, and so, the rest of the class of statements belonging to the language can be on no firmer ground than this undefinable term. [5]

(b) Definition prior to logical truth: The second problem is that we have some sort of circularity. Consider Carnap's notorious example of how to stipulate a "truth by definition" (or in his word, "convention"):

(i) For every x, y and z, if z is the result of putting x for "p" and y for "q" in "if p then q", and x and z are true, then y is true.

This tells us that if we have a true conditional statement with a true antecedent, then the consequent of the conditional is true. Suppose we already know:

(ii) z is the result of putting x for "p" and y for "q" in "if p then q", and x and z are true

then we can infer

(iii) y is true

but only if we use the logic of "if-then". The fourth English word of (i) is "if" and the fifth from the end is "then"; we know that given (i) and (ii) we can infer (iii), because we understand the English expression "if_then_". But this understanding is not provided by (i); rather it must be presupposed by it, in the sense that we can only understand the import of (i) if we already understand the notion if-then. More generally, the statement of definitions cannot be what determines logical truths or logical relationships, because it is only by virtue of logical relationships that logical truths or relationships are derivable from them.

Beyond this, we have another, simpler problem with definition. The fact that we are able to stipulate a definition (such as "every mare is a horse") by no means demonstrates that we have created a truth. What would stop Darwin from stipulating that

(5) species arise by means of evolution

is a definition? In other words: when somebody makes an assertion, what distinguishes it as the creation of a truth by definition, rather than merely as the (true or false) expression of a fact?

We are no closer, then, to finding some way of determining whether a predicate contains a subject, or whether two terms are interchangeable within the right context. What we need is some clear notion of meaning itself.

a) John Stuart Mill suggested that the meaning of a proper name is its reference. Consider:

(6) Morning Star

(7) Evening Star

These terms are co-referential, but do they mean the same thing? Gottlob Frege notes that the discovery that they are one and the same was one of astronomy, not analysis of the meanings of the words; so we cannot accept reference as an explanation of meaning. [6] [7]

b) It is not extension, because

(8) centaur

(9) unicorn

are alike in extension but differ in meaning, and

(10) creature with a heart

(11) creature with a kidney

may also turn out to be co-extensional, even though they differ in meaning.

c) It is not nomination because

(12) "8"

(13) "the number of planets"

name the same abstract entity, but are not synonymous; and conversely because, as noted in the case of (1), a word can have more than one meaning.

d) Meaning is not a phenomenological state, because we may be in different phenomenological states and yet still understand each other. Consider

(14) My uncle became a lawyer yesterday

Two speakers may picture entirely different things when they think of "uncle" or "lawyer" or "yesterday", and yet still altogether understand each other. Some predicates such as "clever" seem to have no corresponding imagery whatsoever. There may be associated imagery, but this is unimportant. There is imagery associated with nonsense-syllables.

e) It is not interchangeability salva veritate. The statements

(15) 'Mare' has four letters

(16) 'Female horse' has four letters

have different truth-conditions. Even excluding the special case of quotation: in an extensional language, the truth of a statement will always depend on the extension of the referents, and not merely on their meaning; in an non-extensional language, we have the same problem with (8) and (9). We might, in a non-extensional language, get a sufficient criterion by prefixing the assertions with some modal term. Consider:

(17) Necessarily, every creature with a heart is a creature with a heart

(18) Necessarily, every creature with a kidney is a creature with a heart

(19) Necessarily, every bachelor is an unmarried man

(20) Necessarily, every unmarried man is an unmarried man

This would seem to give us a criterion of meaning, because (17) and (18) differ in meaning and are not interchangeable; (19) and (20) are alike in meaning and are interchangeable. This might seem to complete the project, if only we could get an explanation of the term "necessarily", but as we saw earlier, no such explanation which would allow us to assert the interchangeability of (19) and (20) has yet been forthcoming.

It may be the case that two terms are synonymous if neither they nor any pair of compounds respectively including them differ in meaning. For instance, (8) and (9) are co-extensional while

(21) Picture of a centaur

(22) Picture of a unicorn

are not, so we get a difference in meaning. However,

(23) Female horse

(24) Mare

are co-extensional and so are

(25) Picture of a female horse

(26) Picture of a mare

so we get a synonymy. If this serves as a criterion for synonymy, then we can build around it a notion of analyticity and necessity.

However,

(27) description of a female horse

(28) description of a mare

differ in extension.

(29) "female horse that is not a mare"

is an example of (27) but not of (28). By this argument, it seems no two terms will ever be synonymous.

Equally, cases (29) and

(30) "mare that is not a female horse"

show that Kant's notion of containment cannot be maintained.

Perhaps we can salvage some notion of meaning from the more specific notion of synonymy (or sameness-of-meaning). So how do we test statements for synonymy?

Peter Strawson and Paul Grice suggested that "two statements are synonymous iff any experience which, on certain assumptions about the truth values of other statements, confirm or disconfirm one of the pair, also, on the same assumptions, confirm or disconfirm the other to the same degree". But this suffers a similar setback to Liebniz' attempt; how can we test a proposition against all experiences? [8]

A suggestion is that two terms of synonymous if they stand for the same Essence or Platonic Idea. This is not much help, as we do not know how to discover whether they do so.

Another suggestion is that two terms are synonymous if they stand for the same mental image. Nelson Goodman notes that "It is not clear what we cannot and cannot imagine. Can we imagine a man 1,001 feet tall? Can we imagine a tone we have never heard?" [9]

A further suggestion is that two predicates P & Q differ in meaning iff we can conceive of something which satisfies P but not Q. What exactly does it mean to conceive something? We can define a five-dimensional body, although we cannot imagine it. But by this criterion we can conceive of a square circle. It might be contested that "square circle" is inconsistent; this leads us around in an obvious circle, however, for the reasons explained near the start of this essay.

Synonymy might be explained in terms of possibility. Two predicates P and Q are synonymous iff there is nothing possible that satisfies P but not Q. However, if we know that all things satisfy (10) and (11), we no longer regard it as possible that there exists something which satisfies (10) but not (11). Proponents of the possibility criterion may protest that there is a non-actual possible which satisfies (10) and not (11). However, it is difficult to accept that there is an entity which we know cannot be actual (because (10) and (11) are co-extensional) yet still retains the status of being possible. Furthermore, this seems to confound the meaning of "is" or "exists" altogether; if an entity is non-actual, then in what sense does it exist?

How are we to determine when there is a non-actual possible for some collection of predicates? It cannot be by testing whether "is P and ~Q" is consistent; because as long as P and Q are different predicates it will be logically self-consistent, and we have no means of determining whether it is otherwise consistent. In fact this latter question amounts to asking whether P and Q are synonymous, so we have come full circle. Hilary Putnam made an attempt to salvage the notion by suggesting a "one-criterion" notion of synonymy, but Jerry Fodor points out that "criterion" is on no better a footing. Furthermore. if a criterion is merely a condition for verification, then we have the same problem which confronts Strawson and Grice. [10] [11]

In conclusion, unless we can get some proper explanation of "meaning" which is not circular and does not rest upon equally dubious terms, let alone of "truth purely by virtue of meaning" then we will not have an adequate basis for supposing that any of our commonly accepted laws of logic, such as "1=1" are analytic. We will simply have to accept that they are facts about our world, and as such they should be treated as scientific theorems.

Footnotes

* Alonzo Church proved that there is no algorithmic means for determining, in arithmetic, whether "x = y", where x and y are arithmetical expressions. Quine claims that it follows that there can be no general means of testing for contradictoriness. [12] [13]

References

[1] Gottfried Wilhelm Liebniz (1714) - "Monadology"

[2] Saul Kripke (1980) - "Naming and Necessity"

[3] Immanuel Kant (1781) - "Critique of Pure Reason"

[4] W.V.O. Quine (1951) - "Two Dogmas of Empiricism"

[5] Rudolf Carnap (1928) - "Der Logische Aufbau der Welt"

[6] John Stuart Mill (1843) - "A System of Logic"

[7] Gottlob Frege (1982) - "The Basic Laws of Arithemetic"

[8] Peter Strawson and Paul Grice (1956) - "In Defense of a Dogma"

[9] Nelson Goodman (1949) - "On Likeness of Meaning"

[10] Hilary Putnam (1983) - Two Dogmas Revisited"

[11] Jerry Fodor (1987) - "Psychosemantics"

[12] Alonzo Church (1936) - "An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory"

[13] W.V.O. Quine (1953) - "On What There Is"

Sunday, 23 January 2011

A Nonexistent Mystery?

The question "why is there something rather than nothing?" has vexed philosophers, theologians and the laity for as long as the history of discourse dates.

Physicist Victor Stenger notes that there is no reason to suppose "nothing" any more likely than "something". To illustrate the point he presses: "Current cosmology suggests that no laws of physics were violated in bringing the universe into existence". [1]

Heat tends to break down the more complex structures of matter into something simpler. Throughout most of the universe, energy is rather more sparse than it is here on earth. Stenger notes that under such conditions, complex structures would tend to last for a much longer period of time, until energy eventually took its toll on matter. Simpler structures tend to be of higher energy and therefore less stable, until they transform into more complex, lower-energy structures. We should be reminded of the second law of thermodynamics: The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum. Stenger suggests that, since "nothing" is the simplest of structures, and has the lowest entropy, it is unsurprising that it could not last forever. Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek concluded, then, that the answer to our question is that "'nothing' is unstable". [1] [2]

We might argue, however, that all of these arguments beg the question. Aren't the laws of physics inferred from the behaviour of the universe itself? And it's debatable whether we can rightly describe "nothing" as having any properties, let alone those of entropy, structure or simplicity. Maybe we are not strictly speaking of "nothing" but only of "nothing physical" or "nothing spatio-temporal" or something similar, which would seem to put us on safer footing. While we're dealing in abstractions, then, let us turn to another proposed answer to our question*.

Phrased succinctly within predicate logic, our next answer goes:

1. | ¬∃x(x=x)

2. | ∀x¬(x=x)

3. ¬¬∃x(x=x)

4. ∃x(x=x)

In English:

1. Suppose that there doesn't exist some thing which is equal to itself.

2. Then, for all things, it is not the case that those things are identical to themselves.

3. Abandon our original hypothesis, then, because it leads to a contradiction.

4. Therefore, there exists some thing which is equal to itself.

The force of this argument is that it claims "Something exists" to be a logical truth; many would claim that, therefore, it is necessarily true by virtue of its meaning**.

It might still be protested that this argument begs the question. It assumes three inferential rules, and it assumes (in dismissing the hypothesis) that self-identity must exist in all things.

The boundless opportunity for making this same style of counter-argument ought to expose the folly of the whole question "why is there something rather than nothing?". If any kind of answer we can give must either be false or circular, then surely we have grounds to dismiss the whole enquiry as a pseudo-question.

Footnotes:

* I am told that this formulation owes to W.V.O.Quine, but I heard of it through a friend Martin Castro-Manzano, who I should duly credit here.

** This I believe to be a mistake; but that is an issue for another post.

References:

[1] Victor Stenger (2007) - "God: The Failed Hypothesis"

[2] Frank Wilczek (1980) - "The Cosmic Asymmetry Between Matter and Antimatter", Scientific American 243, no. 6, p82-90

Tuesday, 11 January 2011

Something You Can Sink Your Teeth Into

Even for those who don't care about the suffering of other species, there's still an overwhelming case to be made against funding the meat industry.

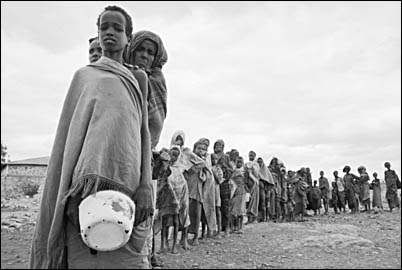

1. Ariable land - the Food and Agriculture Organisation finds that around 90% of deforestation owes to intensive farming and related practices. Livestock production accounts for about 30% of the world's land surface area. Peter Singer (1975) calculates that, if every human ate as much meat as the average American, we'd need 5/3 as much land as the planet can offer. [1] [2] [3]

Free range industries consume more land than intensive industries, acclerating the rate of species extinction. [4]

2. Waste - all animals burn off thermal energy, and so inevitably produce less energy than they consume. For every 8 pounds of protein a pig consumes, it produces 1 pound of protein; for every 21 pounds of protein a calf consumes, it produces 1 pound of protein. [5] [6]

Lester Brown (1974) of the Overseas Development Council estimated that if Americans reduced their meat consumption by 10% it would free up a staggering 12 million tons of edible grain per year - enough to feed 60 million people. Don Paarlberg, a former US secretary of agriculture, claimed that halving the US livestock industry would save enough edible nutrition to feed the nonsocialist developing countries four times over. [7]

Each pound of steak costs the equivalent of 2,500 gallons of freshwater, 5 pounds of grain and a gallon of gasoline. John Robbins (2001) estimated as many as 12,000 gallons of water. More than half of the US water supply is used for livestock. John Farndon (2009) set the figure at 20,000 litres, and estimated that a fifth of the world's freshwater would be needed for a fifth of the human race to eat a quarter-pounder weekly. Meat, more generally, requires about fifty times as much freshwater as the equivalent amount of wheat. [8] [9] [10] [11]

3. Environmental damage - the United Nations (2009) estimated that the livestock industries are responsible for 51% of world greenhouse gas emissions.

An article by the United Nations (2006) asserted: "The livestock sector is...the largest sectoral source of water pollution, contributing to eutrophication, 'dead' zones in coastal areas, degradation of coral reefs, human health problems, emergence of antibiotic resistance and many others."

The local livestock industry accounts for around half of New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions. [12]

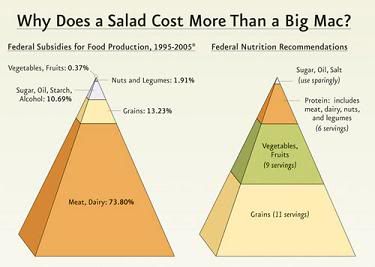

4. Economic impact - the meat industry is ridiculously subsidised*. Economist Nick Louth (2008) estimated that by 2030 everybody in the UK would need to be vegan to prevent a recurrence of economic recession as oil stores are further depleted. [13]

5. Effects on the consumer - vegetarians tend to live longer than meat-eaters**. [14] [15]

Nutritionists are with increasing frequency beginning to recommend vegetarianism: Dr. T. Colin Campbell, nutritional researcher at Cornell University and director of the largest epidemiological study to date, states “The vast majority of all cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and other forms of degenerative illness can be prevented simply by adopting a plant-based diet.”

Many of those who give up meat also report an increase in energy and libido. Vegetarians are less likely to become impotent; Studies have found that meat-eaters rank 13% lower in testosterone than vegans do. [16]

6. Effects on the labourer - the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that, annually, nearly one in three slaughterhouse workers suffers from illness or injury, compared to one in 10 workers in other manufacturing jobs. The rate of repetitive stress injury for slaughterhouse employees is 35 times higher than it is for those in other manufacturing jobs.

Multinational Monitor called Tyson Foods one of the world's "Ten Worst Corporations" because it hires people in the U.S. who are too young to work legally; the same year, Decoster Egg Farms appeared on the list. Secretary of Labour (at the time) Robert Reich said "The conditions at this migrant farm site are as dangerous and oppressive as any sweatship we have seen"***. [17]

In conclusion, it is not necessary to debate whether animals "matter" in this nuance of moral discourse; the case can be made purely on philanthropic grounds.

Footnotes:

* This argument doesn't stand in the case of large meat exporters, such as the USA and Australia. The American Meat Institute claims that it generates 6% of the country's gross domestic product. However, for each pound of meat exported from one country there is a pound imported to another; and when fuel reserves are so diminished as to hinder world trade, the importers will have to find a way to make do without the meat, and the exporters will have to suffer the drop in revenue. This is already a problem in several countries; intensive-rearing corporations move in, sell their cheaply produced meat at a lower tariff and kill off the local agricultural industry. When the parent countries suffer economic troughs, as in recent years, the client countries are left starving and dependent. [18] [19]

** Of the five studies, only the one by Gary E. Fraser overtly demonstrates a causal link between vegetarianism and lifespan. Similarly, there are a plethora of studies showing correlations between vegetarianism and high intelligence quotients, and between meat consumption and violence toward other humans, but the causal links have not been conclusively established.

*** Another entry on the same list was Smithfield Foods, a hog slaughtering plants, having received the largest Clean Water Act fine to date. Rarely a year goes by without a meat-producing corporation appearing on one of these lists for some atrocity or another. [17]

References:

[1] World Rainforest Movement (1998) - "What are the underlying causes of deforestation?"

[2] Alternet (2009) - "13 breathtaking effects of cutting back on meat"

[3] Peter Singer (1975) - Animal Liberation

[4] Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United States - "Cattle ranching is encroaching on forests in Latin America"

[5] Folke Dovring, Scientific American (Feb 1974).

[6] Frances Moore Lappé (1971), pp.4-11

[7] Boyce Rensberger, New York Times (October 25, 1974)

[8] As calculated by Alan Durning of the Worldwatch Institute.

[9] Science News (March 5, 1988), p153

[10] John Farndon (2009) Do You Think You're Clever? p136

[11] G. Borgstrom (1973) pp.64-65

[12] Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, New Zealand - "Voluntary green house gas reporting feasability study"

[13] Andrew Sullivan (2010) - "Daily Dish"

[14] American Journal of Clinical Nutrition - "Mortality in vegetarians and nonvegetarians: detailed findings from a collaborative analysis of 5 prospective studies"

[15] Gary E. Fraser (2001) - "New Adventist Health Study research noted in Archives of Internal Medicine"

[16] Allen NE (July 2000) - "Hormones and diet"

[17] Multinational Monitor (1997) - "Multinational Monitor's 10 Worst Corporations of the Year"

[18] American Meat Institute - "The United States Meat Industry at a Glance"

[19] Multinational Monitor (2008) - "The System Implodes: The 10 Worst Corporations of 2008"

Sunday, 9 January 2011

The War on Movement

The politics of fear is more relevant to the current social climate than most people realise: the primary motive for generating panic is that it tends to attract voters to the right wing [1] [2] [3]. This is not a bona fide proof that such panics are unfounded, of course - but it ought make us a little more skeptical.

Let's consider one of the key debates which might, in modern times, be said to separate the left from the right: immigration. I'll focus, for now, on that which current legislation already attempts to restrict.

1. The Illegal Population: There are an (upper-bound) estimated 8,000,000 illegal immigrants in Europe (as of 2007); some 800,000 more joining the population every year [4].

2. Black Markets: there are many of those who still come and work, yet have no rights. They are made to work in unsafe conditions and payed well under the minimum wage; their bosses may fire them on a whim, and leave them homeless and starving, with no legal protection. Further: Those working on the black market do not pay tax; they still take jobs but provide no public revenue.

Many unauthorised Immigrants have to employ criminal gangs of people-smugglers. People smuggling generates $20 billion (£11 billion) pa in USA, a black market second only to drugs [5].

3. The Economic Benefits of Immigration: it is a principle tenet of Smithian capitalism and monetarism (which the critics of immigration are usually quick to defend) that labour-movement between economies must be as free as capital-movement. Less skilled workers are scarcer in affluent countries; immigration is usually to richer countries, providing labor [4] [6] [7].

The weak argument is often advanced that immigrants are "stealing our jobs"; well this is obviously not so. To increase the population is to increase the demand as well as the supply, and thus, create a new job for each one which is taken. In fact, labourers in rich countries tend to be more productive (due to better technology and a richer infrastructure) [4].

The Journal of Development Economics estimated that the world economy could as much as double from completely unrestricted migration* [8]; more recently, World Development estimated the benefits to be around $55.04trillion [9].

4. The Cost of Border Controls: so what does it cost to keep immigrants out? The Spanish city of Ceuta is only 11.5 square miles in area, but the Spanish government has invested an incredible £200million in keeping Morocco out (not that it has worked) [4] [10].

The cost to the migrants themselves is somewhat more grim: United has documented nearly 9,000 deaths caused by Europe's border policies between 1993 and March 2007 [4]. The Economist estimates that around two thousand people drown annually in the Mediterranean, on their way from Africa to Europe [11].

Proponents make unfalsifiable claims: when original predictions about the war on immigration were falsified, George Bush claimed that more money, technology and resources (raising number of border patrollers to 18,000 between 2006 and 2008, and sending 6,000 national guard to the borders in the meantime) were needed. But funding had quintupled (to $3.8 billion) since 1993, and triple the size of the border control, without a noticeable change in illegal immigraton influx.

5. In conclusion, I might say that illegal immigration is indeed a problem, but that the problem is with the illegalisation, not the immigration.

Footnotes:

* Between 1892 and 1924, during the period in which it rose to financial superiority, America processed 5,000 migrants per day. Around a third of modern Americans can trace their ancestry to these migrants [5]. Let us also not forget the means by which the other two thirds got there.

References:

[1] New Scientist (2010) - "Stranger danger at heart of racial bias"

[2] David Straker (2010) - "Political conversion?"

[3] A perfect example of using fear to generate conformity is Mr. Cameron's quotation in paragraph 8: MSN News (2010) - "Tories attack 'eccentric' Lib Dems"

[4] Philippe Legrain (2007) - "Immigrants: Your Country Needs Them"

[5] New York Times (13 June 2004) - "By a Back Door to the US"

[6] Noam Chomsky (2006) - "Failed States"

[7] Dan Cryan and Sharon Shatil (2009) - "Introducing Capitalism"

[8] C.Hamilton and J.Whalley (1984) - "Efficiency and distributional implications of global restrictions on labour mobility"

[9] Jonathan W.Moses and Bjorn Letnes (2005) - "The economic costs to international labour restrictions"

[10] World Press - "Ceuta, the border fence of Europe"

[11] The Economist (6 October 2005) - "Decapitating the Snakeheads"

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)